Long before we had machines to test air quality, coal miners brought canaries underground. When the canary stopped singing, they knew the air wasn’t safe — they had to leave.

In much the same way, word count per minute has become the “canary in the coal mine” of reading. It’s a quick way to see whether a child is keeping up with expected reading development. Research supports its value: studies have found that oral reading fluency, when measured with norm-referenced tools, is one of the most reliable early indicators of overall reading proficiency and later comprehension (Fuchs, Fuchs, Hosp, & Jenkins, 2001; Hasbrouck & Tindal, 2017).

But just like the canary didn’t tell the whole story of what was wrong—only that something in the air had changed—word count per minute doesn’t tell the whole story of how a child reads. It’s a signal, not a diagnosis.

Reading Fluency Is More Than Rapid Decoding

When we talk about fluency, many educators instinctively think about how fast a child can read — how many syllables, words, or lines per minute.

Fluency, however, isn’t about speed alone. It’s about reading with ease, accuracy, and understanding. A fluent reader recognizes words automatically and reads with natural phrasing and expression. The pace feels comfortable — fast enough to support comprehension, but not so fast that meaning is lost.

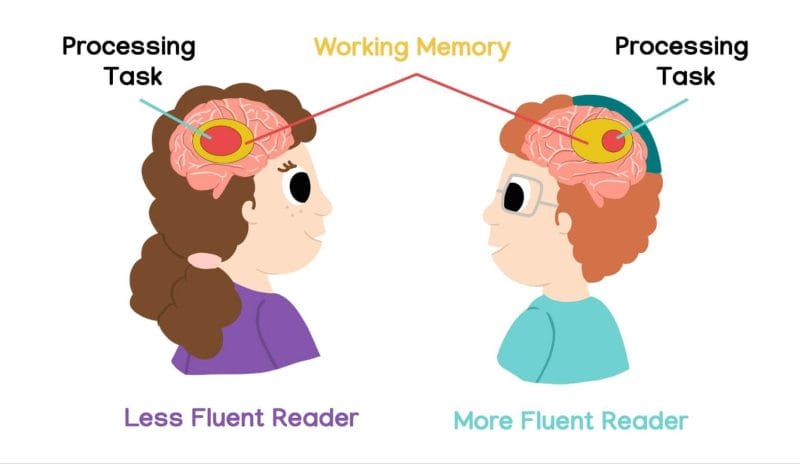

Research consistently shows that fluent reading depends on automatic word recognition, which frees cognitive resources for comprehension (LaBerge & Samuels, 1974; Kuhn & Stahl, 2003). When these elements work together, the reader’s attention shifts from sounding out words to making sense of what they’re reading. They pause when something doesn’t make sense, reread when they need clarity, and use tone to reflect understanding. That’s what fluency really looks like — reading at a rate that supports comprehension, not competes with it.

Putting Word Count in Context

Word count per minute can be a helpful indicator of how efficiently a student reads, but context is very important. We can’t interpret numbers in isolation — we have to consider what kind of words and text the child is reading.

There’s a world of difference between a student reading two-syllable decodable words built from a few familiar vowels, and one reading pesukim from Tehillim filled with multisyllabic words, unfamiliar vocabulary, and complex syntax. These tasks demand entirely different levels of skill and automaticity, so the reading rate will naturally differ as well.

Even within structured practice, reading nonsense syllables, decodable word lists, or connected text draws on different aspects of the reading brain. Children tend to read connected text faster because meaning helps guide and predict word recognition. When words appear without context, every one of them must be decoded from scratch — a much slower and more effortful process.

Valid fluency assessment depends on using grade- and language-appropriate norms (Hasbrouck & Tindal, 2017). In Hebrew reading, this kind of calibration is still emerging. Existing tools such as MaDYK (Mivchan Dinami Shel Y’cholot Kriah), illustrate an important effort to create norm-referenced measures for Hebrew readers in day schools. At the same time, educators must remember that norms only hold meaning when they reflect the learner’s instructional context, language background, and stage of Kriah development.

So while word count per minute can alert us that a student’s fluency deserves attention, it should not stand alone. Especially in Hebrew reading, the type of text, the level of mastery, and the purpose of reading all shape what the numbers really mean.

Fluency Through a Second-Language Lens

Fluency and automatic word recognition work hand-in-hand, freeing the mind to focus on meaning. Automaticity has been found to be one of the strongest predictors of comprehension across languages (Rasinski, 2012; Wolf & Katzir-Cohen, 2001). For children learning to read in a second language, that process can look different — and that’s okay. They may slow down as they retrieve word meanings, translate internally, or try to make sense of unfamiliar structures. That slower pace is not a setback; it’s evidence that they’re monitoring for comprehension. We want that. We want children to think about what they’re reading, not just push through the words.

For second-language readers, reading rate can lag behind decoding accuracy as children draw on two linguistic systems for meaning (Geva, 2006; Koda, 2007). That’s why their reading often sounds more deliberate, even when their accuracy is strong. Over time, as vocabulary, syntax, and familiarity with text structures grow, their pace naturally accelerates — not because they’ve practiced speed, but because comprehension has caught up with decoding.

Fluency and comprehension work in tandem — a simultaneous process in which each strengthens the other. As decoding becomes more automatic, understanding deepens; as comprehension grows, reading flows more naturally. When a child reads fluently, the experience feels balanced. The words come smoothly, the meaning unfolds naturally, and there’s room left in working memory for imagination, inference, and reflection. Together, fluency and comprehension move in harmony toward joyful, effortless reading.

Seeing the Whole Reader

To truly understand a reader, we have to look at more than speed. We have to see the interplay between accuracy, expression, comprehension, and motivation. Fluency isn’t just mechanical — it’s emotional and cognitive. A child’s tone, confidence, and stamina all tell part of the story.

That’s why we created the Hebrew Scouts Kriah Fluency Rating Scale — a tool that helps educators look beyond syllables per minute to see how children actually engage with text. It allows us to notice not only how quickly they read, but how accurately, expressively, and meaningfully they do so.

Because at the end of the day, reading fluency is more than rapid decoding. It’s the harmony of accuracy, expression, and understanding that transforms reading from an exercise into an experience.

References

-

- Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., Hosp, M., & Jenkins, J. (2001). Oral reading fluency as an indicator of reading competence: A theoretical, empirical, and historical analysis. Scientific Studies of Reading, 5(3), 239–256.

-

- Geva, E. (2006). Second-language oral reading fluency and reading comprehension: Implications for assessment and instruction. Scientific Studies of Reading, 10(1), 1–30.

-

- Hasbrouck, J., & Tindal, G. (2017). Oral Reading Fluency Norms: Updated and Expanded.

- Hasbrouck, J., & Tindal, G. (2017). Oral Reading Fluency Norms: Updated and Expanded.

-

- Koda, K. (2007). Insights into second language reading: Cross-linguistic perspective. Cambridge University Press.

-

- Kuhn, M. R., & Stahl, S. A. (2003). Fluency: A review of developmental and remedial practices. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 3–21.

-

- LaBerge, D., & Samuels, S. J. (1974). Toward a theory of automatic information processing in reading. Cognitive Psychology, 6(2), 293–323.

-

- Rasinski, T. V. (2012). Why reading fluency should be hot! The Reading Teacher, 65(8), 516–522.

-

- Wolf, M., & Katzir-Cohen, T. (2001). Reading fluency and its intervention: Implications for the reading brain. Scientific Studies of Reading, 5(3), 211–239.