As published in EMBRACE Magazine, Volume 2, Issue 3

One out of every seven children has a literacy learning challenge. If you imagine a typical classroom with twenty students, there would likely be at least three students who struggle with literacy acquisition. Although many times they could hide it well, I bet you all remember classmates or friends who did not have an easy time learning to read. Maybe you just recall children who were not “book smart,” or who struggled to keep up in various subjects. Literacy learning differences, such as dyslexia, are extremely prevalent.

Most reading challenges are due to a deficit in phonological processing or symbol imagery. Phonological processing includes the awareness of the sound system that makes up our language, including syllables, rhymes, and distinct letter sounds (phonemes). For example, in order to spell the word sprint, a learner needs to hear all six individual sounds in the word. In order to understand that kamatz beis is ‘buh’, a learner needs to have some rhyming and initial sound awareness. Phonological processing also includes memory and speed. Many learners may know the letter names and letter sounds; however, their retrieval process is slow, which can make reading a slow and laborious process. Symbol imagery challenges other learners when it comes to working with symbols, where they confuse b, d, p, and q, or they confuse similar words such as through, though, and thought. Their brain is not yet efficient in working with and remembering symbols, impeding their ability to read successfully.

Dyslexia is a two-sided coin. Both of these processing deficits have nothing to do with a learner’s overall intelligence. On the contrary, many people with reading challenges are extremely intelligent and accomplished. Many of the world’s most famous scientists, engineers, inventors, and artists have been known to have dyslexia. Dyslexia is a two-sided coin. While many dyslexics have a deficit on the left side of the brain which is in charge of memorizing facts such as letter sounds or multiplication tables, most dyslexics are stronger on the right side of the brain which is in charge of reasoning, creating, and visualizing, and this is where they excel.

Before the printing press, if one had a deficit in phonological processing or symbol imagery, it would not matter. Most of society’s function was not literacy-based. If we think back to the era when the Gemara was written down, we would remember that most of the process was oral. Even if a pupil was not fully literate, he would still be able to participate in learning because most of the learning was centered around oral discourse. However, today, so much of our society is text-based that a literacy challenge can have a serious impact on a student’s educational and professional success. Many people today still gauge intelligence based on the way others read and write, assuming that a couple of spelling errors indicates that the writer may have a hard time understanding and remembering. To me, a spelling challenge would indicate that the writer must be smart in a different way. It makes me curious.

MY WORK

What drives me to help exceptional learners is that I, too, struggled with literacy acquisition. I have endless patience with my students because I see myself in them. I am motivated to work with all kinds of learners using approaches that are most suitable for them.

My clinical practice in Crown Heights is where I work with students to figure out why they may be struggling with literacy acquisition. I then use an array of resources and strategies to design and implement an intervention that would allow the learner to reach grade expectation in the most enjoyable and efficient way possible.

I also work with educators. One of my pet projects is helping educators learn how to screen children for the early signs of literacy learning risks, beginning in kindergarten. Our hope is to identify these children as early as possible and to close the gap before it widens. In my experience working with older children and adults, the work is much more daunting when there is years’ worth of learning that needs to be caught up. Academic failure can take a toll on a child’s confidence, resilience, emotions, and behaviors; early intervention is crucial.

When it comes to English literacy, there are mountains of research, standards, textbooks, published programs, and blogs available for new teachers and experienced clinicians. This is a stark contrast to what is available for Lashon Hakodesh literacy, or kriah. While there are a handful of educators who are scientifically exploring how to teach Lashon Hakodesh as a foreign language, we have yet to create a supportive and informative system for educators to follow. We have yet to prepare materials that would meet the needs of all kinds of learners, across the grades.

After more than a decade immersed in English instruction, I came to Lashon Hakodesh instruction armed with insight and training in the literacy learning process. Obviously, this instruction was different as it had an added component. I wasn’t just teaching literacy. I was teaching Torah.

An important key to reading successfully is having an understanding of the text. The rush of pleasure that a child experiences when they successfully read a story that they understand is its own reward.

There is a misconception that using traditional Mesorah is outdated and will not work for many children. In a sicha, the Rebbe addressed those who believe that following alternate methods of teaching Alef Beis and Nekudos seems to be more effective. To this, the Rebbe said,

“Not as those who mistakenly claim that by using the Mesora’dike method we slow down the child’s development and progress in reading. This is not true, for the opposite is true!”

In the past, children were struggling because they did not understand what they were reading. They were not getting the natural feedback they would hear if they were familiar with how the language is supposed to sound. I find that adding the language aspect to the Mesorah approach solves the issue. Written language is supposed to piggyback on spoken language. Logically, children should be frequently exposed to Lashon haTorah in order for them to understand what they are reading, and receive the reward for decoding a word or a phrase properly.

Additionally, being that the Lashon Hakodesh letters are holy, unlike English literacy, literacy in Lashon Hakodesh is not a means to an end. Learning the letters is an end in and of itself. It is for this reason that the many Gedolei Yisroel have emphasized the importance of using the Mesorah’s method when teaching children how to read Lashon Hakodesh.

After days and weeks of exploration, I had amassed a collection of word activities and stories that have a lot of picture support, and I used them in conjunction with the traditional method for kriah. The results were beautiful. I saw changes in children’s reading behaviors faster than I had ever expected. Children who were held back a grade because of their literacy challenges experienced leaps and bounds of success in a matter of weeks. The next steps were to share this method with other educators and to fill any gaps so this system would be feasible and easy to use. And BH, I am thankful for the opportunities that I have had to share my practices with other parents and educators.

WHEN SCIENCE AND TORAH MEET

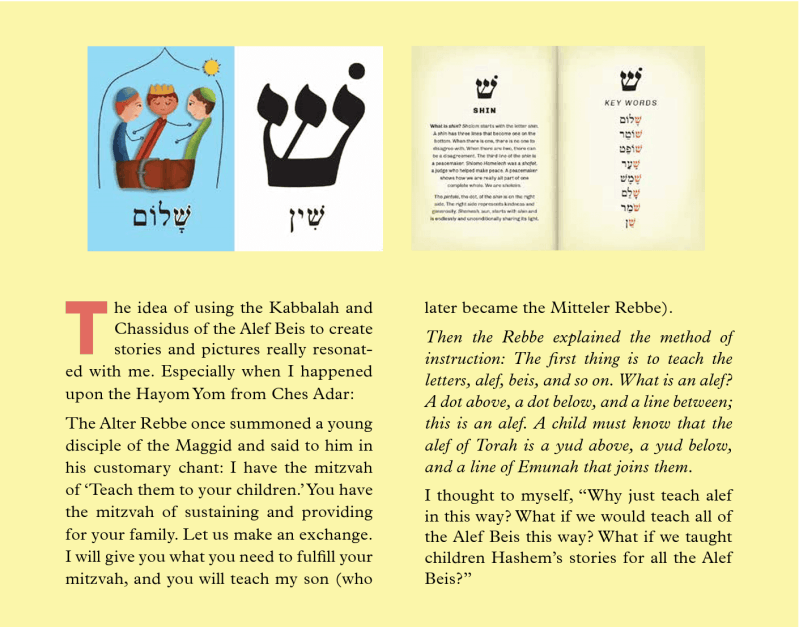

To help learners remember the alphabet, one of the most effective methods I use is called embedded pictures. It is a technique that pairs letters with a picture, allowing the learner to make a memorable association between the two. We then remove the picture, and the learner can still remember the letter. Basically, the learner is able to use visual memory for pictures to compensate for a deficit in memory for symbols. I wanted to use this technique for the Alef Beis, but I could not find anything suitable for young learners. I found beautiful materials for more mature learners, and I found resources for English mnemonics, but I wanted Lashon Hakodesh mnemonics that would be appropriate for the youngest learners.

I wasn’t sure if the embedded picture method would conflict with Mesorah. With the help and knowledge of Rabbi Levi and Baila Risha Goldstein, we realized there was a way to do this right.

AT FIRST

I began sculpting miniature objects for each letter story. Some of my middle school students were interested in making their own sets. One student even sold two sets to educators! The experience was so meaningful and empowering for these learners because they were able to use their talents to learn and share the Alef Beis on a deeper level. More encouraging, there was an interest from educators to have similar resources in additional learning environments. I had to make it reproducible. I reached out to Esty Raskin, a graphic artist and Bais Rivkah alumna, and asked her if she would illustrate these letter stories with me. She showed me a sample of the letter Alef and I knew right away that she was the right person. I loved her Alef. I loved the way she wrapped the light around the Torah! It really demonstrated the true essence of the story.

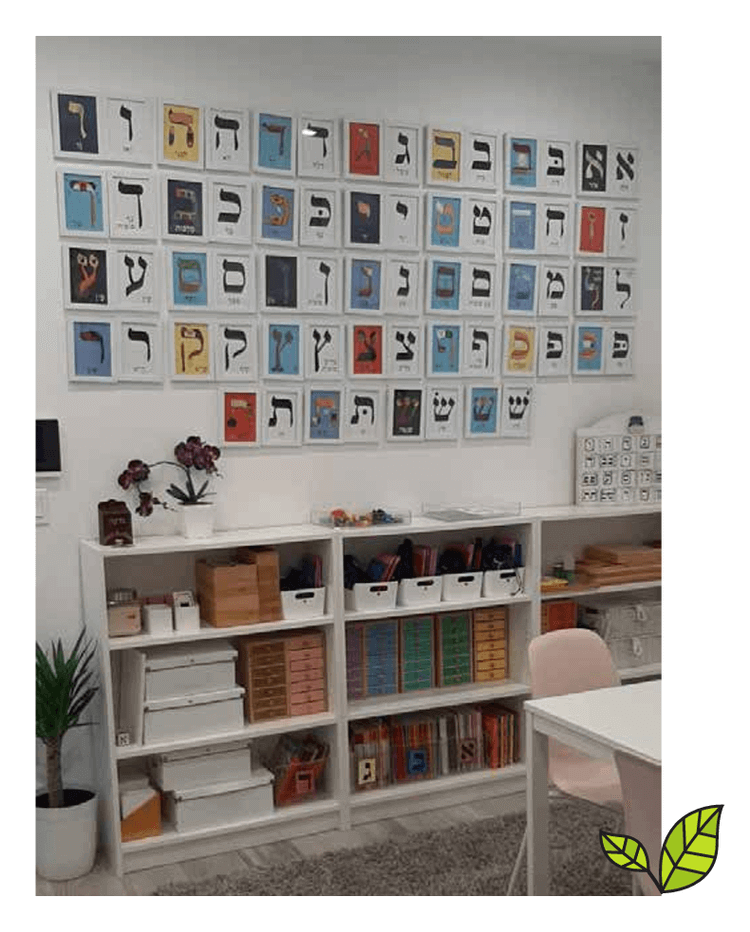

THE ALEF BEIS CARDS

FIRST THE SIDDUR LETTER:

When Hashem gave us the Torah, the letters were of black fire atop white fire. Therefore, according to Jewish tradition, the Alef Beis should first be introduced using black letters on a white background.

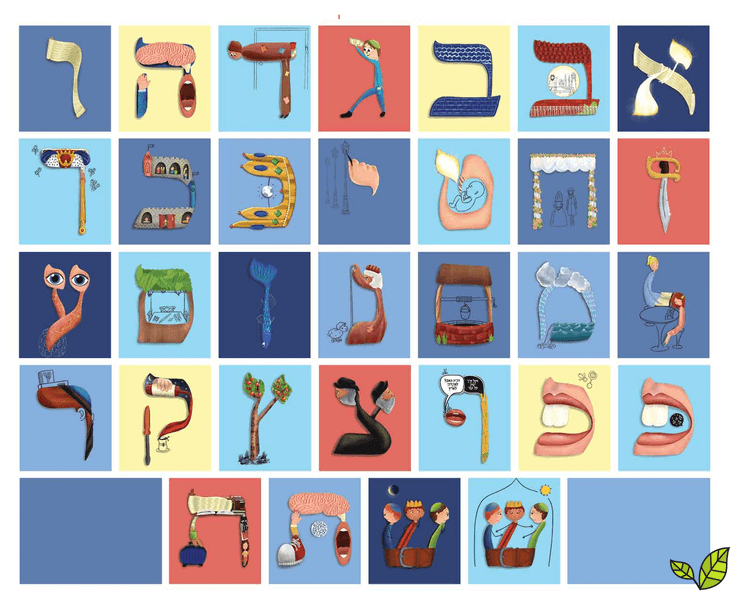

THE ILLUSTRATION:

Esty and I worked ceaselessly to create these thought-provoking renderings of each letter incorporating its “story.” We wanted each drawing to truly express the story of the letter while making sure the illustration was clearly recognizable as a letter. Some were easy, such as the mem. The water cycle was a natural fit with the circular shape of the letter, and mayim is a basic word that many children know. Other letters were quite challenging, but we knew we would get it right. We were determined to fully love each letter. Our first attempt for the letter yud, a yad, was a hand holding a lulav and esrog, symbolizing unity. It didn’t look good and it didn’t feel right. We brainstormed, we looked back in the seforim, and we got it. The letter yud is a neshama, the pintele Yid, whose purpose is to be a lamplighter, to help another. Esty drew the hand lighting a lamp, and we knew right away it was perfect. The picture looked great and it told the true story of the letter.

THE KEY WORD: LESSONS FOR LIFE

Many may think that using Lashon Hakodesh keywords may be too ambitious and lofty. How could we use unfamiliar words, especially with such young children or children with language deficits? Children can master these new words using a few different techniques. Exposure to the new vocabulary will familiarize them with these new Lashon Hakodesh words, helping them absorb the meanings just as easily as the names of ice cream flavors, or of their favorite toy characters. Additionally, most of the keywords are important terms that children may already know or they should learn. Words like echod (one), bayis (house), ayin (eye), or peh (mouth) are really good words to know. Finally, to understand the job of Alef Beis, children need to learn early on that Lashon Hakodesh letters are used to create words in Lashon Hakodesh. We would not illustrate the usage of beis with a ball; we would demonstrate usage with a Lashon Hakodesh word. We also emphasize the holy energy that each letter has, and how each letter is a building block in Hashem’s continuous creation of the world.

THE STORIES

My challenge was to capture the essence of the letter without overwhelming my target audience. I had to sift through a myriad of beautiful lessons and focus only on the most essential components. Some mind-blowing stories are told in just the sequence of the letters. The ches, tes, and yud tell us about the purpose of life: ches is a story of a chuppah, tes is a pregnancy, and yud is the neshama, the baby. It was difficult to omit some very interesting concepts, but it proved possible with the hope that there would be future opportunities to learn more about the letters.

LESSONS FOR LIFE

Learning Alef Beis can be an experience of its own. Each story is a lesson for learners to apply to their own lives. Young children would benefit from having the time and support to understand and internalize the concepts of the letters. For example, with the letter beis, children can relate how when they learn Torah and do Mitzvos, they can actually feel the goodness and light filling their environment. With the letter gimmel, children can relate to their own acts of kindness. Learners would benefit from taking the time to demonstrate their comprehension of the letter’s story, by drawing, painting, or sculpting, or by engaging any other forms of art and discourse.

ASKING FOR HELP

I often stress the importance of asking for help. Admitting that we can’t do something on our own can be difficult, but having the ability to ask for assistance is a life skill. We all need additional support at times. I am no exception.

Each step of creating these cards became possible for me with the guidance of others. When I began by doing research, I quickly realized that the best sources of information were seforim. To be honest, I can only read Lashon Hakodesh with nekudos and I did not have the vocabulary to understand the kabbalistic concepts. I was fortunate to have my mother help me with some further research. Among many things, she helped me understand the spiritual differences between shin and sin, beis and veis, and between the regular letters and the f inal letters.

To help bolster my limited spelling and writing abilities, I sent the work to two editors and a professional writer. My website was the result of hiring a web designer. I had spent time puzzling over the instructions and trying to figure out the technology, but I finally conceded defeat. There is always that inner conflict between trying to be independent and knowing when to ask for help.

ALL KINDS OF LEARNERS AT HEART

Now that this project is completed and available for the public, I have a few next steps that I hope to work on. We have been developing a tabletop version with mini cards that would provide learners with hands-on opportunities for practice. These tabletop cards are almost ready for market. We are also planning on making group-sized posters, journals, storybooks, and more. I would also love to film tutorials on how to create the clay miniatures. Young children love exploring and manipulating miniature objects.

I plan on using these same cards to make Lashon Hakodesh prefix mnemonics. The same stories that we used for the Alef Beis can be used to help children remember the Lashon Hakodesh prefixes. Mem is water, water is the source of all life, everything is from water. Mem means “from.” Beis is a house. The purpose of a house is to protect what is inside. Beis means “in.”